Halo braces treat upper cervical spine fractures and serve as the most rigid form of external immobilization. Recently, halo braces have lost favor due to known complications and advances in surgical stabilization. This study aims to determine the contemporary incidence for use of halo braces and identify risk factors associated with mortality in trauma patients undergoing halo brace for cervical spine fractures.

Materials and methodsThe 2017–2019 Trauma Quality Improvement Program Database was queried for patients ≥18 years-old with a cervical spine fracture undergoing halo brace. Patients sustaining penetrating trauma and severe torso injuries (abbreviated injury scale >3 for the abdomen or thorax) were excluded. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed.

ResultsFrom 144,434 patients with a cervical spine fracture, 272 (0.2%) underwent halo brace and 14 (5%) of these died. Those who died were older (73.5 vs. 53 years-old, p = 0.011) and had higher rates of hypertension (78.6% vs 33.1%, p < 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (14.3% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001). Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 (46.2% vs. 8.2%, p < 0.001) and cervical spinal cord injury (71.4% vs. 21.3%, p < 0.001) were more common in patients who died. In addition, those who died more often sustained respiratory complications (7.1% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.004) and sepsis (7.1% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.004). On multivariable logistic regression analysis, only Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 (OR 19.77, 3.04–128.45, p = 0.002) was associated with increased mortality.

ConclusionsOnly 5% of cervical spine fracture patients undergoing halo brace died. Respiratory complications and sepsis were more common in those who died. On multivariable analysis only Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 remained an independent associated risk factor for mortality.

Los aparatos ortopédicos Halo tratan las fracturas de la columna cervical superior y sirven como la forma más rígida de inmovilización externa. Recientemente, los aparatos de halo han perdido popularidad debido a complicaciones conocidas y avances en la estabilización quirúrgica. Este estudio tiene como objetivo determinar la incidencia contemporánea del uso de aparatos ortopédicos con halo e identificar los factores de riesgo asociados con la mortalidad en pacientes traumatizados sometidos a aparatos ortopédicos con halo por fracturas de la columna cervical.

Materiales y métodosSe consultó la base de datos del Programa de mejora de la calidad del trauma 2017–2019 para pacientes ≥18 años con una fractura de la columna cervical sometidos a un halo ortopédico. Se excluyeron los pacientes que sufrieron traumatismos penetrantes y lesiones graves del torso (escala de lesión abreviada >3 para el abdomen o el tórax). Se realizaron análisis de regresión logística bivariados y multivariables.

ResultadosDe 144,434 pacientes con fractura de columna cervical, 272 (0.2%) fueron sometidos a halo y 14 (5%) de ellos fallecieron. Los que fallecieron eran de mayor edad (73.5 vs. 53 años, p = 0.011) y tenían mayores tasas de hipertensión (78.6% vs. 33.1%, p < 0.001) y enfermedad renal crónica (14.3% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001). La escala de coma de Glasgow ≤8 (46.2% frente a 8.2%, p < 0.001) y la lesión de la médula espinal cervical (71.4% frente a 21.3%, p < 0.001) fueron más comunes en los pacientes que fallecieron. Además, los que murieron con mayor frecuencia sufrieron complicaciones respiratorias (7.1% frente a 0.4%, p = 0.004) y sepsis (7.1% frente a 0.4%, p = 0.004). En el análisis de regresión logística multivariable, sólo la Escala de Coma de Glasgow ≤8 (OR 19.77, 3.04–128.45, p = 0.002) se asoció con una mayor mortalidad.

ConclusionesSólo el 5% de los pacientes con fractura de columna cervical sometidos a halo fallecieron. Las complicaciones respiratorias y la sepsis fueron más comunes en los que murieron. En el análisis multivariable sólo la Escala de Coma de Glasgow ≤8 siguió siendo un factor de riesgo asociado independiente para la mortalidad.

The development of the halo brace in 1959 by Perry and Nickel revolutionized the treatment of cervical spine injuries.1 As the most rigid external immobilization device available, the halo brace consists of a circular metal frame that is anchored directly to the patient's skull with metal pins. This frame is further supported by a vest worn on the torso, which enhances stability. The halo brace has some data demonstrating efficacy in various clinical scenarios such as the postoperative stabilization of the cervical spine, and most notably, the management of traumatic injuries to the upper cervical spine.2,3

Despite its longstanding use, the reliance on the halo brace has seen fluctuations, influenced by the evolving approaches to managing traumatic spine injuries.4 While the halo brace continues to remain a tool utilized for the non-operative management of cervical spine injuries, there is growing concern over its complication rates, which have been reported to be as high as 46.3% in all age groups and over 66% in elderly patients.5,6 Complications range from pin loosening and localized infections to pressure sores, pneumonia, and dysphagia.7–9 In addition, mortality rates with the use of the halo brace have historically ranged from 6 to 8.3%.5,8

Therefore, it is essential to identify risk factors associated with increased mortality in trauma patients with cervical spine fractures undergoing the application of a halo brace to help guide clinical decisions, inform patient counseling, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. This study aimed to use a contemporary national database to evaluate the incidence of the use of halo bracing and identify independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients undergoing halo brace for traumatic cervical spine fractures.

MethodsThis retrospective cohort study was performed utilizing the Trauma Quality Improvement Program database, a multicenter database that collects prospective trauma data from over 900 trauma centers throughout the United States.10 This study was deemed exempt by our institutional review board, and a waiver of informed consent was granted due to the use of this deidentified national database.

The 2017–2019 Trauma Quality Improvement Program database was queried for adult trauma patients (≥18 years) with a cervical spine fracture who underwent halo brace application. Patients with penetrating trauma and severe torso injuries (abbreviated injury scale >3) were excluded. Two groups were compared by the primary outcome of mortality: those who survived versus those who died. Secondary outcomes such as hospital length of stay, intensive care unit length of stay, and ventilator days were also collected.

Demographic variables collected included age, sex, and comorbidities such as cerebral vascular accident, congestive heart failure, hypertension, peripheral artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Additional variables included current smoking status, anticoagulant use, and steroid use. Data collected on injury profile included the mechanism of injury (i.e., pedestrian struck, fall, motor vehicle collision, motorcycle collision), injury severity score >15, and Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤8 on arrival. Vital signs on arrival were also collected including tachycardia (heart rate >120 beats per minute), hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), and tachypnea (respiratory rate >22 breaths per minute). Additionally, data on in-hospital complications including cardiac arrest, intubation, any respiratory complication, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and sepsis were collected.

The two cohorts were compared using Chi-square and Mann–Whitney U tests. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independently associated risk factors for mortality. Variables for this analysis were determined by author consensus along with review of the literature.5–9 Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 29, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines.11

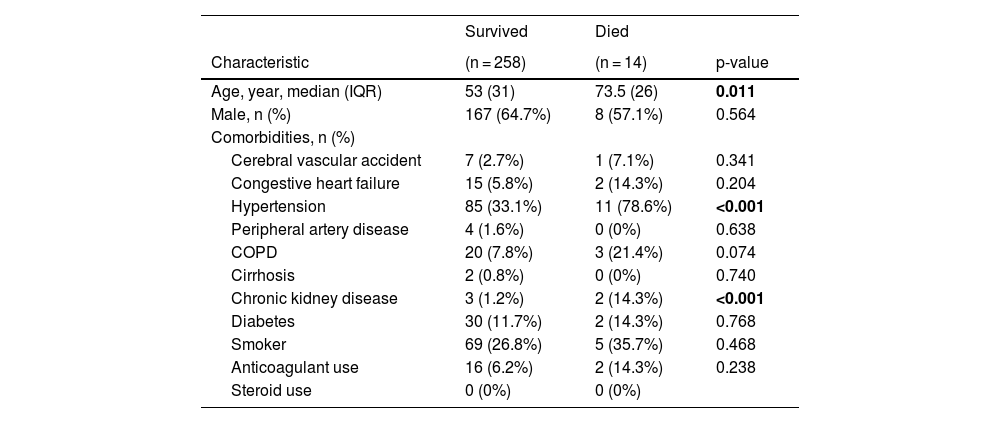

ResultsStudy populationFrom the 144,434 patients with a cervical spine fracture, 272 (0.2%) underwent halo brace application. Among these patients, 14 died (5%). Patients who died were older (73.5 vs. 53 years old, p = 0.011), more commonly presented after a fall (64.3% vs. 37.6%, p = 0.046), and had higher rates of hypertension (78.6% vs. 33.1%, p < 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (14.3% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001) compared to those who survived (Table 1).

Demographics and comorbidities of patients undergoing Halo brace for cervical spine fracture stratified by mortality.

| Survived | Died | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n = 258) | (n = 14) | p-value |

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 53 (31) | 73.5 (26) | 0.011 |

| Male, n (%) | 167 (64.7%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.564 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Cerebral vascular accident | 7 (2.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.341 |

| Congestive heart failure | 15 (5.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.204 |

| Hypertension | 85 (33.1%) | 11 (78.6%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.638 |

| COPD | 20 (7.8%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.074 |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.740 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (14.3%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 30 (11.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.768 |

| Smoker | 69 (26.8%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0.468 |

| Anticoagulant use | 16 (6.2%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.238 |

| Steroid use | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

IQR = interquartile range, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Bold entries represent statistical significance at p < 0.05.

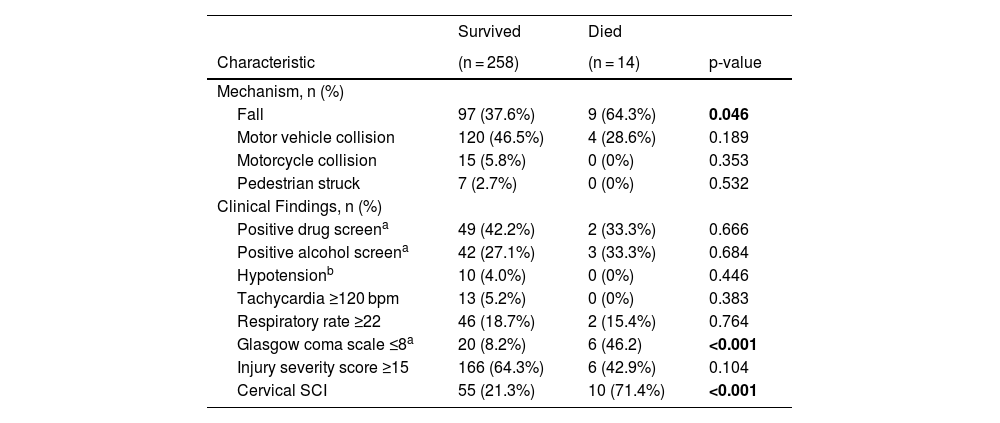

Patients who died had higher rates of cervical spinal cord injury (71.4% vs. 21.3%, p < 0.001) and more commonly presented with Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 on arrival (46.2% vs. 8.2%, p < 0.001) compared to patients who survived. There were no differences in injury severity score and vital signs on arrival between cohorts (Table 2).

Injury profile and vital signs for patients undergoing Halo brace for cervical spine fracture stratified by mortality.

| Survived | Died | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n = 258) | (n = 14) | p-value |

| Mechanism, n (%) | |||

| Fall | 97 (37.6%) | 9 (64.3%) | 0.046 |

| Motor vehicle collision | 120 (46.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | 0.189 |

| Motorcycle collision | 15 (5.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.353 |

| Pedestrian struck | 7 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.532 |

| Clinical Findings, n (%) | |||

| Positive drug screena | 49 (42.2%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.666 |

| Positive alcohol screena | 42 (27.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0.684 |

| Hypotensionb | 10 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.446 |

| Tachycardia ≥120 bpm | 13 (5.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.383 |

| Respiratory rate ≥22 | 46 (18.7%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0.764 |

| Glasgow coma scale ≤8a | 20 (8.2%) | 6 (46.2) | <0.001 |

| Injury severity score ≥15 | 166 (64.3%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.104 |

| Cervical SCI | 55 (21.3%) | 10 (71.4%) | <0.001 |

Bpm = beats per minute; SCI = spinal cord injury.

Bold entries represent statistical significance at p < 0.05.

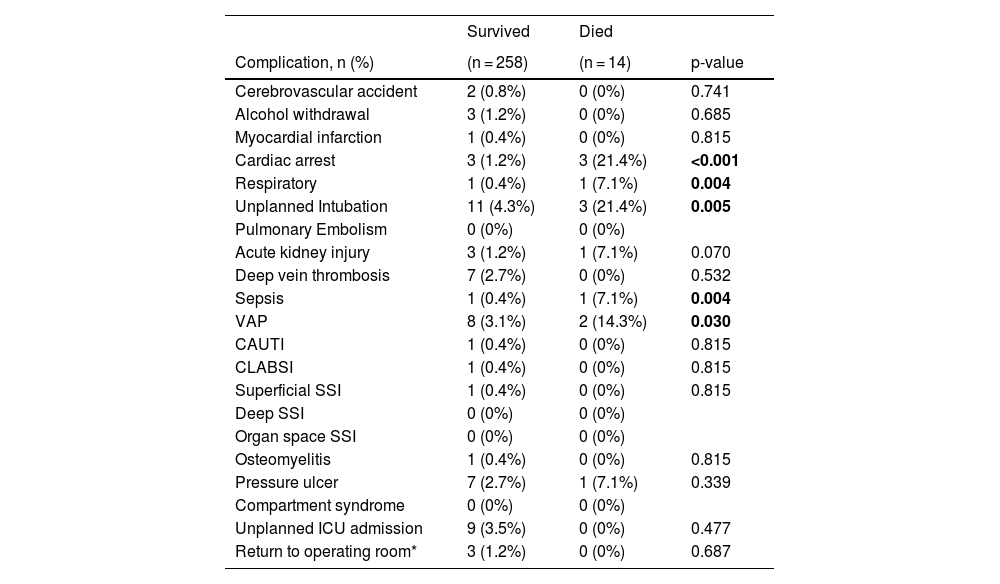

Regarding in-hospital complications, patients who died had higher rates of cardiac arrest (21.4% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001), unplanned intubation (21.4% vs. 4.3%, p = 0.005), respiratory complications (7.1% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.004), sepsis (7.1% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.004), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (14.3% vs 3.1%, p = 0.03) compared to patients who survived (Table 3).

Outcomes and complications for patients undergoing Halo brace for cervical spine fracture stratified by mortality.

| Survived | Died | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Complication, n (%) | (n = 258) | (n = 14) | p-value |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.741 |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 3 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.685 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.815 |

| Cardiac arrest | 3 (1.2%) | 3 (21.4%) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.004 |

| Unplanned Intubation | 11 (4.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0.005 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Acute kidney injury | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.070 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 7 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0.532 |

| Sepsis | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.004 |

| VAP | 8 (3.1%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0.030 |

| CAUTI | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.815 |

| CLABSI | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.815 |

| Superficial SSI | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.815 |

| Deep SSI | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Organ space SSI | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Osteomyelitis | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.815 |

| Pressure ulcer | 7 (2.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0.339 |

| Compartment syndrome | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unplanned ICU admission | 9 (3.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.477 |

| Return to operating room* | 3 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.687 |

SSI = surgical site infection, OR = operating room, ICU = intensive care unit, VAP = ventilator associated pneumonia, CAUTI = catheter-associated urinary tract infections, CLABSI = central-line associated bloodstream infection.

Bold entries represent statistical significance at p < 0.05.

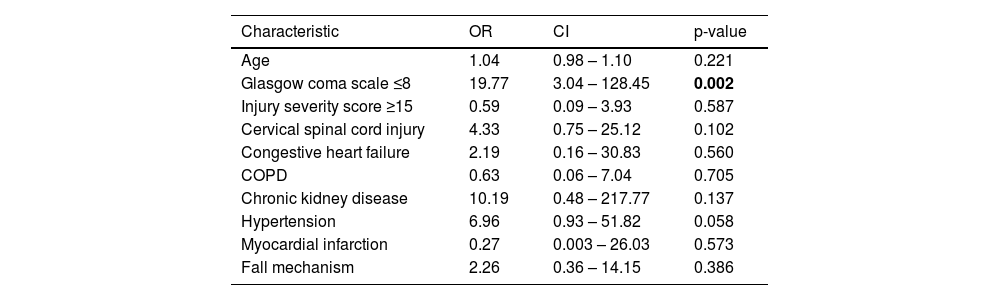

On multivariable logistic regression analysis, only a Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 on arrival (OR 19.77, 3.04–128.45, p = 0.002) remained an independently associated risk factor for increased mortality in patients who underwent halo brace for traumatic cervical spine fractures (Table 4).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for associated risk of mortality for patients undergoing Halo brace for cervical spine fracture.

| Characteristic | OR | CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 | 0.98 – 1.10 | 0.221 |

| Glasgow coma scale ≤8 | 19.77 | 3.04 – 128.45 | 0.002 |

| Injury severity score ≥15 | 0.59 | 0.09 – 3.93 | 0.587 |

| Cervical spinal cord injury | 4.33 | 0.75 – 25.12 | 0.102 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.19 | 0.16 – 30.83 | 0.560 |

| COPD | 0.63 | 0.06 – 7.04 | 0.705 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10.19 | 0.48 – 217.77 | 0.137 |

| Hypertension | 6.96 | 0.93 – 51.82 | 0.058 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.27 | 0.003 – 26.03 | 0.573 |

| Fall mechanism | 2.26 | 0.36 – 14.15 | 0.386 |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Bold entries represent statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Halo brace application is an option for treating cervical spine injuries, but it is not without potential complications.7–9,12,13 As such, it is prudent to identify risk factors that would help predict poor outcomes when opting for halo brace application. This national database study spanning three years of data found that patients who died following halo brace application for traumatic cervical spine fracture were older, had higher rates of certain comorbidities and spinal cord injuries, and more often on arrival presented with a Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8. However, only Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 was found to be an independently associated risk factor for mortality.

Despite known complications, halo brace application continues to be an effective form of treatment for cervical spine fractures with high clinical success rates.3,12,13 This contemporary national analysis identified a mortality rate of only 5% for patients with cervical spine fractures undergoing halo brace, slightly lower than previous reports of 6–8.3%.5,8 It is important to highlight that significantly higher rates of mortality ranging from 13 to 42% have been found in older patients when compared to younger patients treated with halo immobilization.6,14,15 A study by Tashjian et al. that included elderly patients with odontoid fractures found a mortality rate of 42% in patients who received halo immobilization compared to 20% in patients who received internal fixation or rigid cervical orthosis.6 Our study adds to the existing literature by demonstrating that age in itself is not an independently associated risk factor for mortality. This is congruent with more recent reports that suggest frailty is a more important indicator of poor outcomes in trauma patients, rather than age alone.16,17

Proper patient selection is vital when tailoring treatment for best patient outcomes. Our current study suggests that additional caution should be exercised when applying a halo brace to patients with depressed Glasgow Coma Scale on presentation. Our study also demonstrates increased rates of comorbidities such as hypertension and chronic kidney disease in those who died following halo brace application. However, on multivariable analysis, these comorbidities were not independent predictors of mortality, similar to some prior studies comparing survivors and non-survivors of halo brace application.6,15 Regarding associations between Glasgow Coma Scale on arrival and mortality in patients receiving halo immobilization, most data have been limited to elderly populations. In a study comparing outcomes of elderly and young cervical spine fracture patients receiving various treatment modalities, Glasgow Coma Scale on arrival was not found to be significant between survivors and those who died within the elderly halo immobilization subgroup.15 In a follow-up study evaluating predictors of in-hospital morbidity and mortality, similarly, Glasgow Coma Scale score on arrival was not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors of halo bracing.6 This suggests in older populations that factors related to frailty and comorbidities may be the strongest predictors of death. Whereas in a generalized adult population such as our study, depressed Glasgow Coma Scale may be highly predictive of mortality with a nearly twenty-fold increased associated risk of death with a Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 on arrival. While a discrepancy exists between the results of our study and existing literature, our study represents a more recent analysis of this association and is strengthened by its generalized nationwide population of trauma patients.

Notably, there are several limitations to our study including those inherent to its retrospective database design such as missing data, coding errors, and lack of granularity. Also, the Trauma Quality Improvement Program database used for this study does not include pertinent information including timing of the halo brace application, variations in device manufacturing, temporal data regarding mortality, and rationale for the decision to use a halo brace instead of cervical collar or surgical fixation. In addition, despite using a large national database, there was a relatively low sample size and a low rate of the primary outcome of death, which may impact the assessment of risk factors for mortality. Also, the study lacks information on important factors related to mortality such as social determinants of health,18 trauma frailty indices,19 and information pertinent to the severity of cervical spine fractures such as the Subaxial Cervical Spine Injury Classification and Severity Score System or other recognized injury assessments.20 Finally, the study lacks post-discharge data as well as important patient-centric outcomes such as return to baseline function and quality of life.

This national analysis found the rate of mortality associated with trauma patients with cervical spine fractures undergoing halo brace to be only 5%. The only independent associated risk factor for mortality in this cohort was a Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 on arrival. This finding may help providers decide whom to consider halo brace application for and counsel patients and their families. Future multicenter prospective research is needed to validate these findings and determine which patients, if any, benefit from halo brace application instead of cervical orthotics or surgery.

Statements and declarationsThe authors have no competing interests or financial disclosures.

Declarations of interestNone.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.