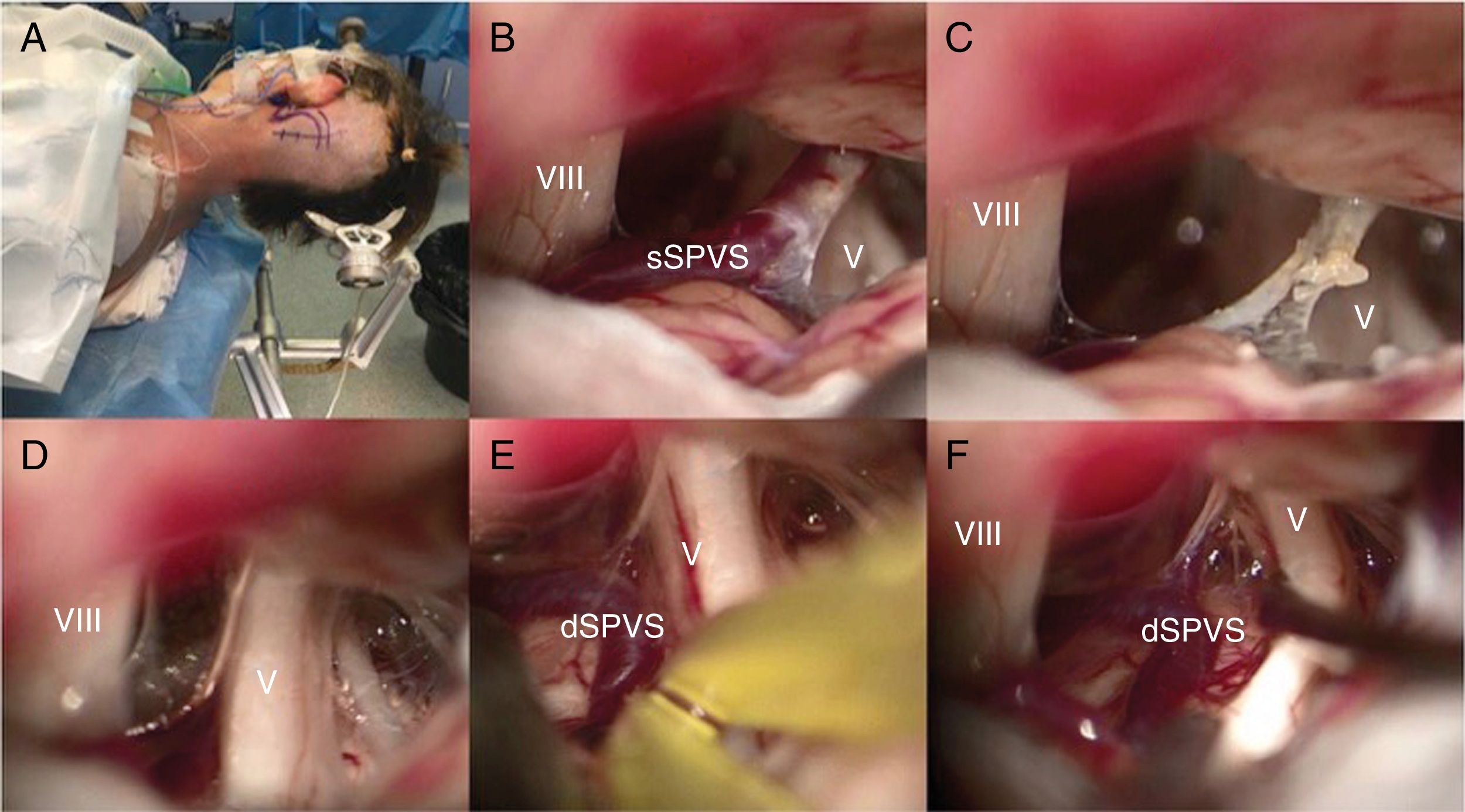

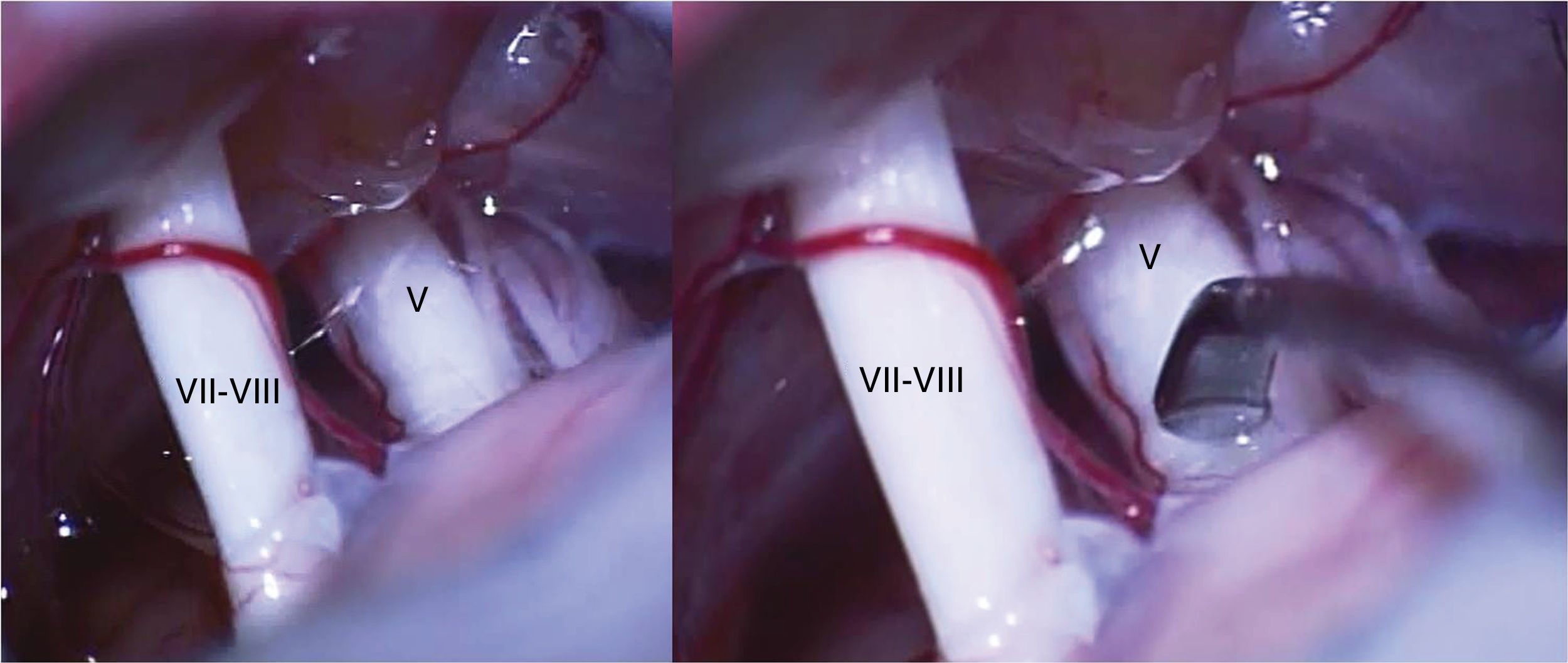

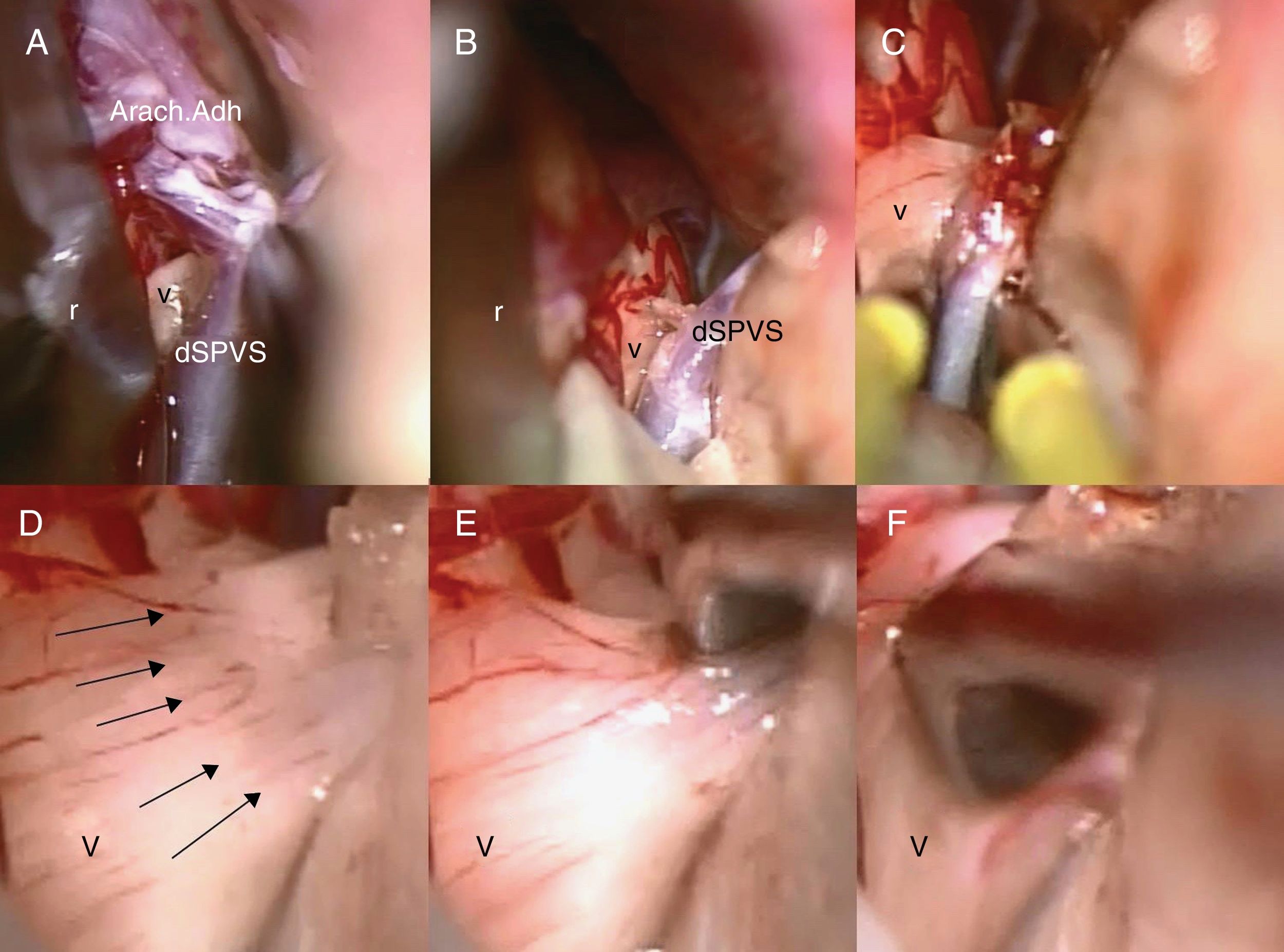

During the microsurgical exploration of trigeminal root in the pontocerebellar angle in patients with primary trigeminal neuralgia (TN) without an evident arterial compression, the surgeon is in an engaged situation because there are not well-established surgical strategies. The aim of this study is to describe in these cases the surgical maneuver we call “trigeminal root massage” (TRM).

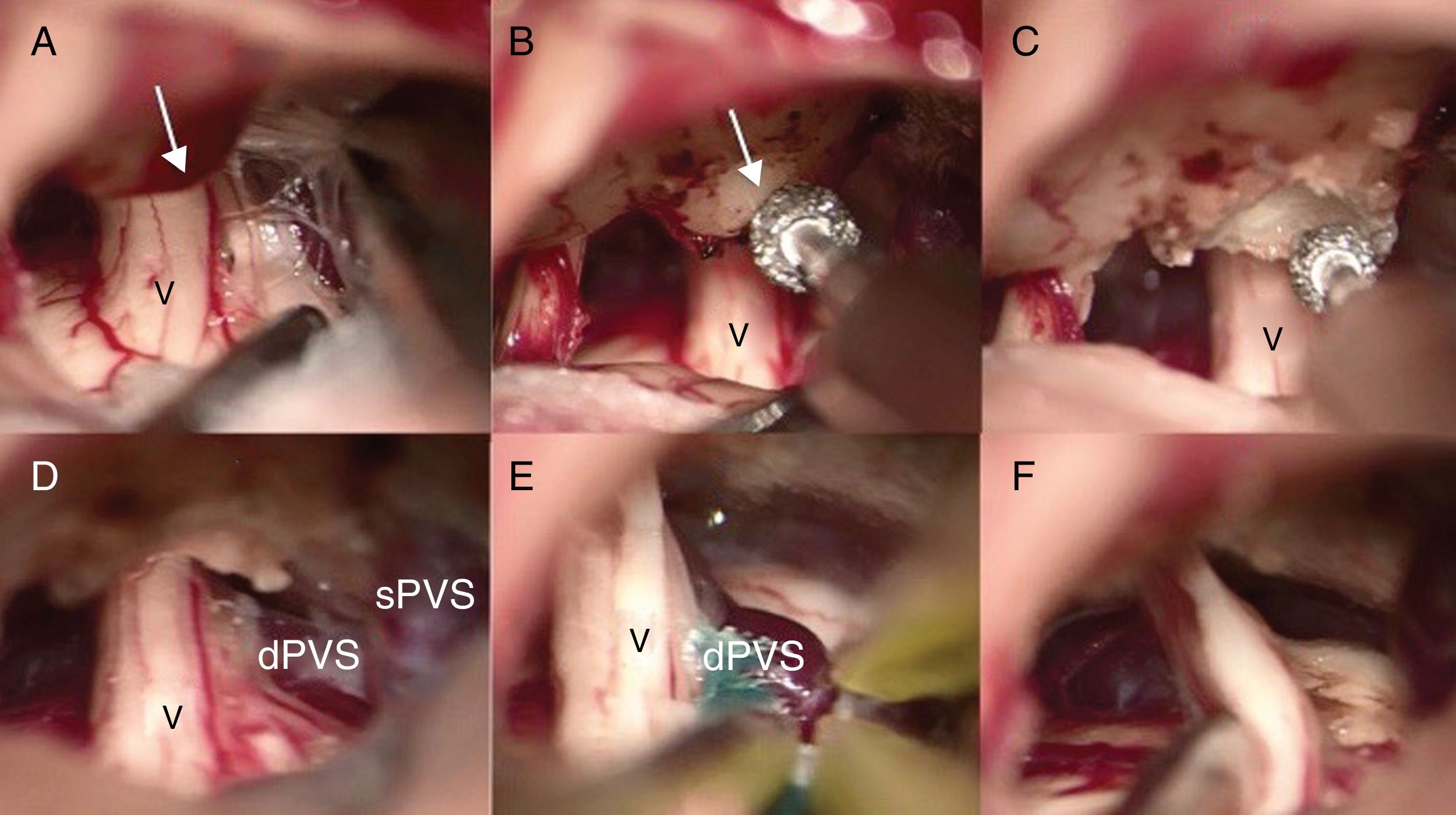

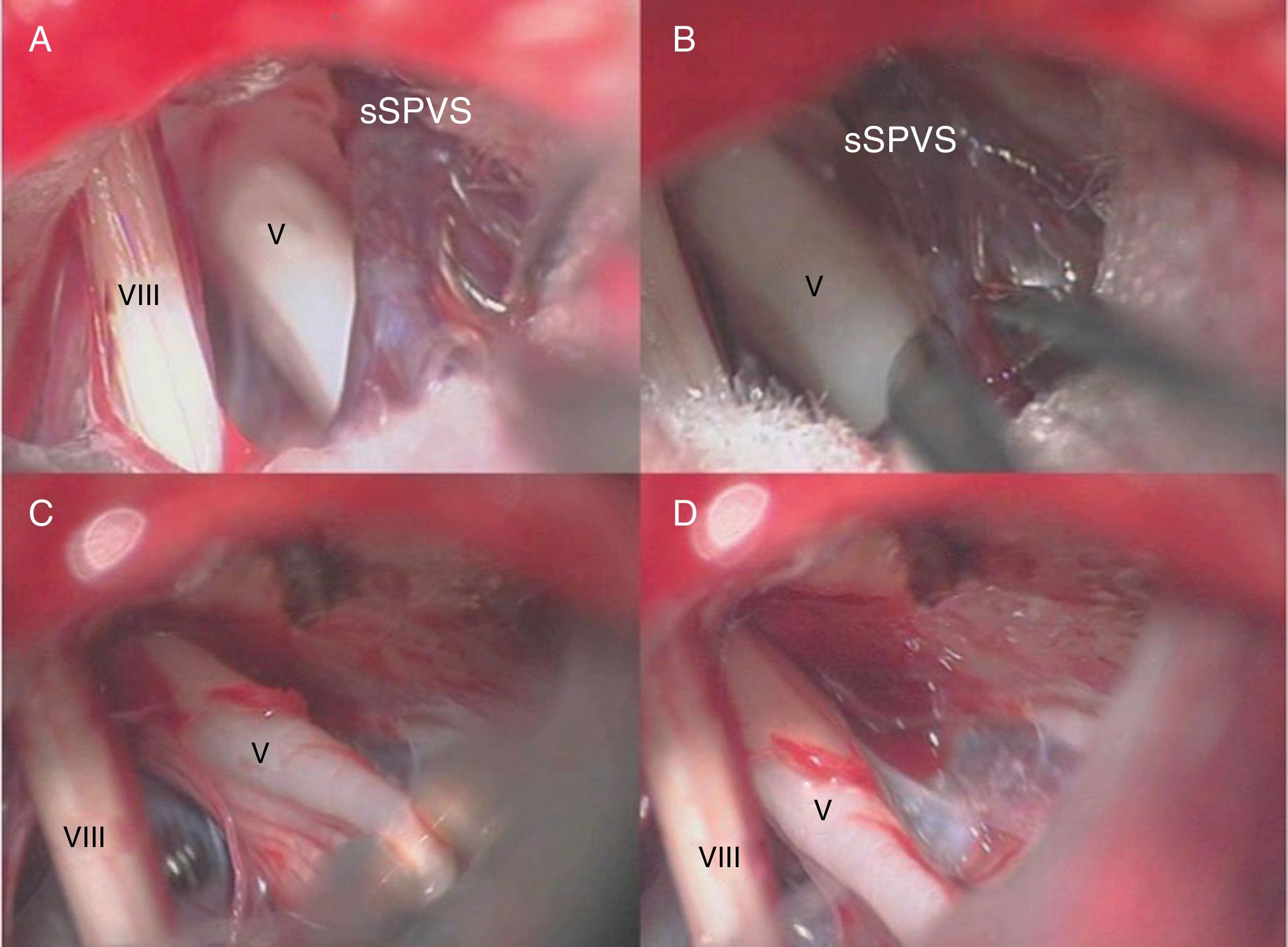

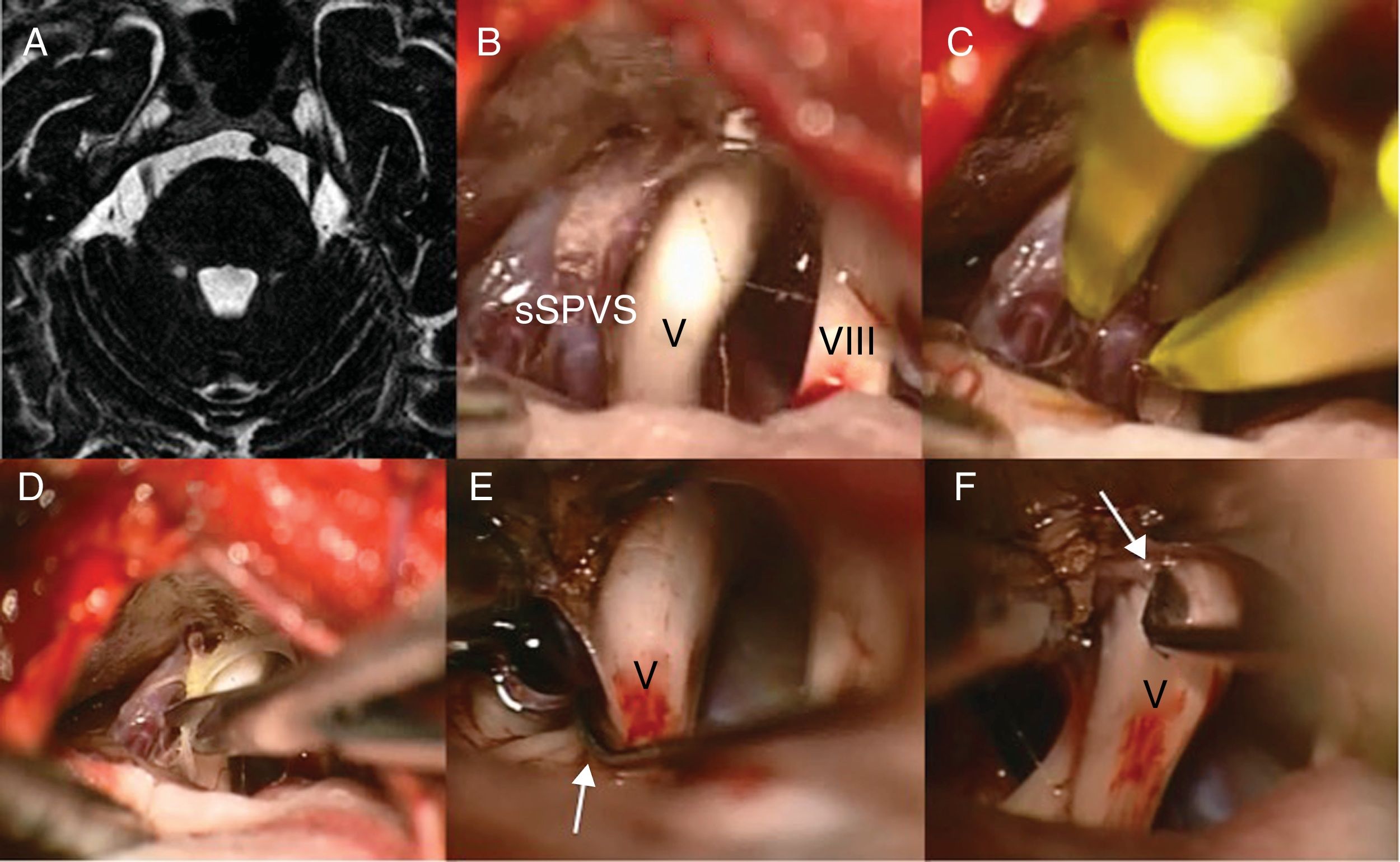

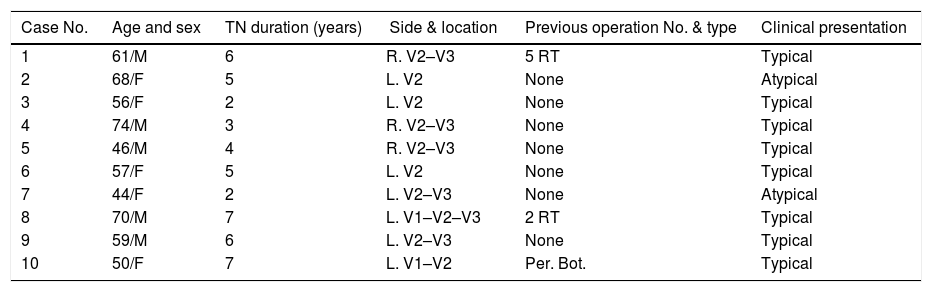

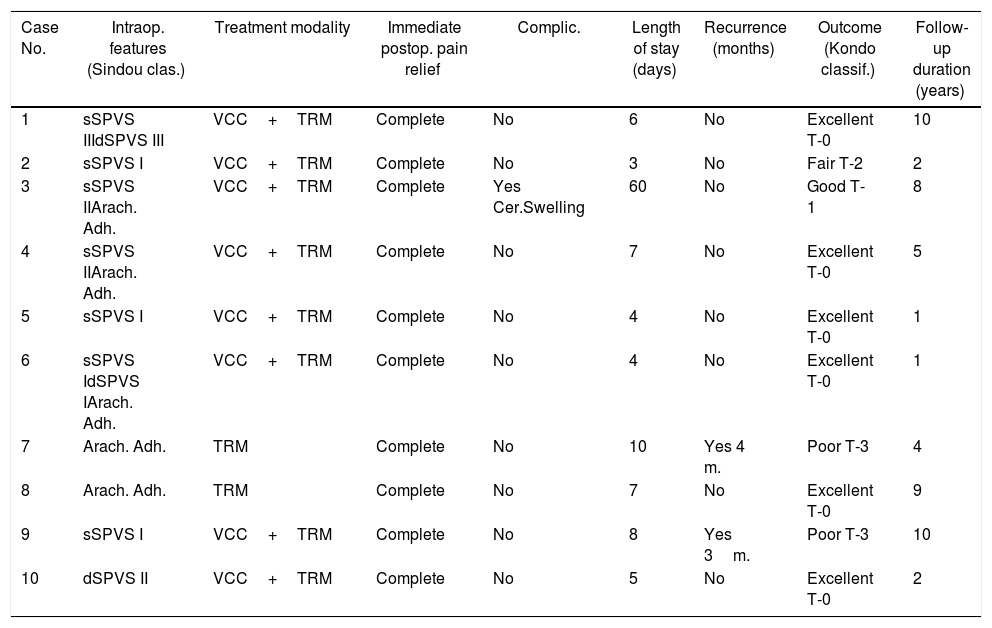

Methods52 consecutive patients with primary trigeminal neuralgia who had undergone a microsurgical suboccipital retrosigmoid exploration of trigeminal root were reviewed. Among them we found 10 patients without an evident arterial compression after a thorough microsurgical exploration. In the great majority of these 10 cases, we noticed a venous contact to the trigeminal root along this cisternal trajectory, in most cases we have had to coagulate the compressive vein/s and then cut. All underwent a simple trigeminal root massage, without interposition of any material implant.

ResultsAll 10 patients experienced immediate pain disappearance and the postoperative course was uneventful except one case with a severe complication: cerebellar swelling, meningitis and hydrocephaly. The recurrence rate was 40%. Six patients achieved pain relief without specific medication with an average follow-up period of 5 years. There have been no mortalities nor any postoperative anesthesia dolorosa.

ConclusionsThe described maneuver provides an easy and simple alternative way in cases where during a microsurgical exploration of trigeminal root, where we don’t find a clear arterial compression, with similar results than other possibilities such as partial sensory rhizotomy or more complicated and time consuming surgery as “nerve combing”. Nevertheless, a 40% of pain recurrence after an average follow-up of 5 years means that is a good alternative, but not a definitive technique at the moment for permanent cure of trigeminal neuralgia without arterial compression.

Durante la exploración microquirúrgica de la raíz trigeminal en el ángulo pontocerebeloso en pacientes con neuralgia del trigémino (NT) primaria sin una evidente compresión arterial, el cirujano se encuentra en una situación comprometida, ya que no existe una estrategia quirúrgica establecida. El objetivo de este estudio es la de describir en esos casos una maniobra quirúrgica que llamamos «masaje de la raíz trigeminal» (MRT).

MétodosSe revisan un total de 52 pacientes consecutivos con NT primaria a quienes se ha realizado una exploración de la raíz trigeminal por vía suboccipital retrosigmoidea. Entre ellos hemos encontrado 10 pacientes sin una evidente compresión arterial durante la exploración microquirúrgica. En 8 de los 10 casos ha existido un contacto venoso de la raíz trigeminal a lo largo de su trayectoria cisternal, procediendo a la coagulación y sección de la/s vena/s. En los 10 casos se ha procedido, finalmente, a un suave masaje de la raíz trigeminal sin interposición de ningún material.

ResultadosLos 10 pacientes experimentaron una inmediata desaparición de la neuralgia y el curso postoperatorio fue favorable excepto por un caso de complicación severa con edema cerebeloso, meningitis e hidrocefalia. La recidiva fue del 40%. Seis pacientes obtuvieron una desaparición completa de la neuralgia, sin medicación específica, en un seguimiento medio de 5 años. No ha habido mortalidad ni anestesia dolorosa postoperatoria.

ConclusionesLa maniobra quirúrgica descrita es una alternativa útil y sencilla en casos donde, durante la exploración microquirúrgica de la raíz trigeminal, no encontramos una clara compresión arterial, con resultados similares a otras posibilidades como la rizotomía parcial o más laboriosas como la llamada nerve combing. En cualquier caso, un 40% de recidiva dolorosa a los 5 años significa que, aunque es una buena alternativa, no es una técnica definitiva en la curación de todos los enfermos con NT sin conflicto arterial.

Artículo

Si es la primera vez que accede a la web puede obtener sus claves de acceso poniéndose en contacto con Elsevier España en suscripciones@elsevier.com o a través de su teléfono de Atención al Cliente 902 88 87 40 si llama desde territorio español o del +34 932 418 800 (de 9 a 18h., GMT + 1) si lo hace desde el extranjero.

Si ya tiene sus datos de acceso, clique aquí.

Si olvidó su clave de acceso puede recuperarla clicando aquí y seleccionando la opción "He olvidado mi contraseña".